An Illuminated Manuscript from Poo

by Eva Allinger

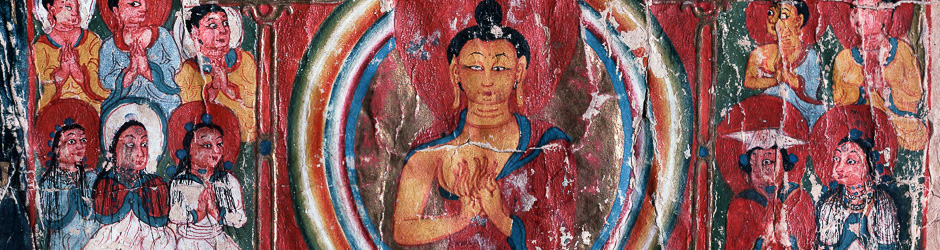

Poo village also preserves an unusual volume of an Aṣṭasāhasrikā-Prajñāpāramitāsūtra manuscript in Tibetan translation. The Book contains chapters one to five, that is approximately a third of the whole text. It has 325 pages (paper, 22x73 cm, 10 lines per page). From page three onwards every page is illustrated on the front side (recto, measuring approximately 6.8x7 cm). Stylistic comparisons to the wall paintings of the nearby Nako temples suggests an attribution of the manuscript to the first half of the 12th century. The ◊ Poo Manuscript gallery collects all illuminations of this manuscript arranged in succession.

In principal early Tibetan manuscripts follow Indian palm leaf manuscripts in format and usage, with the rings indicating the area where the rope is supposed to hold the pages together preserved as a remnant. However, material and size differ considerably from Indian examples as does their concept of illustrations. In both Indian and Tibetan manuscripts it is not the text that is illustrated. While Indian manuscripts mostly feature the eight main events from the live of the Buddha and/or configurations of deities, the concept of the Poo manuscript is completely different. After the first two pages with larger, more numerous, detailed and diverse illustrations the same motive of a seated Buddha is repeated over and over again.

My contribution to the festschrift Vanamālā focuses on the process of illustrating the manuscript by comparing the repeated Buddha depictions in detail. In this way a a workshop production process was discovered for the first time in this cultural area. Confronted with the necessity of creating hundreds of illustrations the manuscript was illustrated by a group of artists of different accomplishments at the same time. It is possible that an artist that worked on the paintings of Nako began with the illustration of the manuscript (page 7) and others worked following his example. In principal four groups of main groups of illustrations can be differentiated: pages 3 to 114, pages 115 to 229, pages 230 to 309 and pages 310 to 324.

It can be demonstrated that the pictures where not done by one artist alone but by a group. Once the outlines of the image was established in red one painter made the face and the figure of the Buddha. Other artists painted the folds of the dress, the halo and the lotus. The group process can be deducted from overlaps and mistakes and also from the fact that differences in the detailing of the dress are found independently of other elements such as the face or the halos. Pages 22 and 23, for example, share the decorative folds in the modelling of the dress but the area of the eyes is drawn completely different. There are also motives found in several of the main groups differentiated above demonstrating that the artists worked at the same time and finished the manuscript within a reactively short period.

- Allinger, Eva. 2006. Künstler und Werkstatt am Beispiel des westtibetischen Manuskriptes in Poo, Himachal Paradesh. In Vanamālā, Festschrift Adalbert J. Gail, edited by Klaus Bruhn, and Gerd J.R. Mevissen. Berlin: Weidler. 1-8, 12 figs.